Making moonshine may seem romantic, but the reality is a much harsher story, filled with crime and heartbreak. Detroit’s long love story with whiskey has both shaped and reflected the greater American relationship with whiskey.

Detroit Vineyards?

Before the Scots came, it was mostly brandy. In fact, Detroit’s European settlement is thanks in part to Antoine Cadillac’s insistence that the land would be the perfect location for vineyards rivaling the greatest Burgundian producers. Just a few years after making these claims, Cadillac was exiled from the settlement and found guilty of smuggling, extortion, and illegal alcohol sales. Brandy was king in Detroit for many years; it was valuable in the world market, potent, and it aged well on the long journey into the interior. Once the British took over, they brought with them a taste for whiskey, as well as a similar penchant for avoiding taxes and excises.

By the 1830s, Scottish and especially Irish settlers were arriving in numbers, bringing a taste for the peated and pot-stilled whiskies of their home countries. The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 opened the Great Lakes to the cities of the eastern seaboard. In 1838, a 22-year-old arrived in Detroit from Douglas, Massachusetts. Young Hiram Walker tried — and failed — at several careers in the bustling frontier town until he finally made a go of it as a grocer with a store at the foot of Woodward Avenue, right along the riverside docks that brought in his imported sugar, cheese, coffee, and tea. Pretty soon, he developed a knack for distilling vinegar for his customers. It was a short jump from there to distilling whiskey, a far more profitable venture.

From Detroit to Canada

Walker started selling his Club Whisky as early as 1850. When an 1855 Michigan state law forbade anyone but chemists from producing whiskey in the state, he moved operations across the river to a strip of land on the Windsor side. He had good timing; since most American whiskies were distilled and barreled in Southern states, the onset of the Civil War disrupted distilling, storing, and shipping all over the U.S. It was far easier to row a mile across the river than it was to navigate the war-torn Southern countryside in search of quality booze.

Walkerville (as it was officially named in 1869) was a company town through and through. And Hiram loomed over all. In the words of a contemporary, Walker was “a unique municipal figure, being practically the mayor, common council, board of public works, fire department, lighting and water works manager.” By 1882, Walkerville held over 600 full-time residents, a church, and a school. One person who never became a Walkerville resident was Walker himself. He chose instead to build a mansion in Detroit and traveled daily by private ferry to his distillery.

In 1865, Hiram Walker was the first distiller to put whiskey into individually sealed and labeled bottles. Of his plan, he wrote, “We will make a fine whisky, and we do not wish it to be confused with inferior products. We will also brand each barrel, so that discriminating patrons can trust its quality.”

The Origin of Canadian Club

Always a genius at marketing, Walker capitalized on his brand to tout quality and recognition. Frustrated, several American distillers convinced the government to require that all products sold in the United States bear their country of origin prominently. Thus, in 1880, Club Whisky became Canadian Club Whisky. Far from sullying Walker’s whiskey’s image, the new label added a foreign flair to the product, and Walker’s success dramatically increased. By 1893, Walker dominated the global whiskey market.

Both Walker’s reputation for quality and his ferry came in handy just a few years later, once Prohibition went into effect. In 1929, 500 to 600 cars per hour were crossing from Detroit to Walkerville. With such proximity to Canada and its distilleries, Detroit was the epicenter of Midwestern bootlegging. And, as the first major American city to go Dry in 1918, Detroit was also the test case for American Prohibition efforts.

From Beer to Whiskey

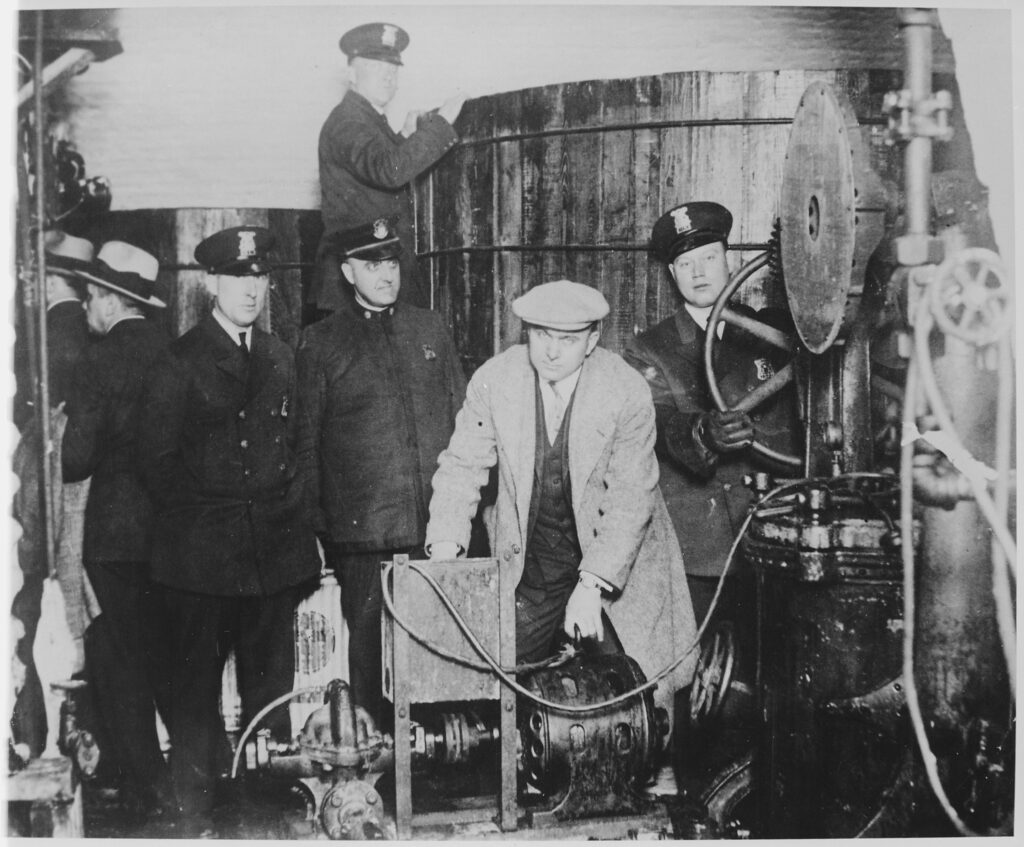

By many accounts, Detroiters failed that test. In 1919 American Magazine reported, “When a man can buy for five dollars a still with which he can make whiskey, it is going to be very hard to stop the manufacture entirely.” In fact, Prohibition managed to turn some beer drinkers into whiskey tipplers. Since it was so expensive to produce and transport anything alcoholic, bootleggers concentrated on the higher-proof items like whiskey rather than wine or beer. A Congressional hearing in 1919 found “former beer drinkers have become whiskey drinkers” and “more whiskey is being drunk under prohibition in Detroit than was drunk under license.” Detroit had twice as many arrests for drunkenness in its first full year of Prohibition (1919) as it had the previous year.

The Repeal of Prohibition

Prohibition, too, signaled the birth of many cocktails as we know them. Although cocktails and punch had been around a few decades by the turn of the 20th century, cocktail culture was born from the need to disguise the taste of rotgut whiskey and moonshine. Detroit had it marginally better than much of the Midwest, with its easy access to Canadian distilleries, railroad shipments, and quick transport by boat and automobile, even airplane. But it was still a great relief when Michigan became the first state to vote to Repeal in 1933.

I Welcome Your Feedback

This is not a story about bourbon, and it is probably not interesting to a lot of people. However, having grown up in Detroit, Detroit whiskey history is one subject that I was truly interested in. Let me know if you enjoy this type of historical information. Your comments are always welcome. Have an idea for a blog post, let me know by commenting or Email.

That was a solid story!! Familiar with the name Hiram Walker, but not his roots, nor did I realize the impact Canadian whiskey had in Detroit.

Don, great story as always!

Thank you Kevin. It was great to see you at the tasting.

Thanks Dan. From vinegar to whiskey. I love the story of anticipating American prohibition and exploiting Canadian prohibition.

Who knew?! Fascinating! Thanks

Thanks Kate. Your input is important.

Nice article! Love a bit of History.

Thanks Don, I appreciate your feeback.

History is always interesting

Great story. I use to drive by their plant all the time but never knew the story. Thanks.

Thanks for the comments. I love that Hiram Walker distilled vinegar before whiskey.